Theater, as all other art forms, defines a part of what it means to be human. Although I may not understand the lives of other animals, I still tend to assume that the difference between living as a human and living as an animal is rather large. Even though both do basic things for survival while striving to raise the next generation, where some animals may even perform better than humans, what makes humanity unique is some ritual that is performed by none but humans—art, which is the real representation of a large sum of the human wisdom.

Once having carefully mused over this matter, one may find that much more dynamicity and complexity are added to life as a result of the existence of art. Art has existed since the day the humans had the urge to improve their lives and have “lifestyles” because “style” is essentially an artistic concept that demands aesthetic judgments and creativity. People live in houses of different styles but not uniform caves; people wear different styles of clothing, eat different styles of food, have different styles of recreational activity…etc. Human nature has an artistic tone as well—people have different styles of personality and prefer different styles of behavior. The drive of humans to want to be unique and different entails style, which in turn entails art.

Therefore, the previous establishment makes it clear that art is really a part of the fundamental building blocks of human nature, deeply embedded in how things operate within our society—people simply have been too accustomed to this and take art for granted. They do not notice art until it is put into more explicit and sensible forms—such as visual art renderings, sculptures, music and of course, theater performances. However, what happens next is rather ironic—people acknowledge theater as art, and embrace the artistic experience when (and perhaps only when) they attend a theatrical event, and they forget that theater really originated from their lives to begin with! Most people view life as rather spontaneous and theater as entirely fabricated and contrived.

However, I must be careful to avoid overgeneralizations, and perhaps people do acknowledge the cousin relationship between theater and life. This may appear in sayings such as, “today was a dramatic day” or “she is overacting a bit.” This kind of acknowledgement makes appearance in language habits, but perhaps people do not quite stop to think about the relevance of theater to life (until they take this class, presumably). Therefore, at this point, I would like to reflect upon the dramatic structure and how people operate themselves in daily lives.

People, like the protagonists in a play, should be goal driven at all time. This goal can be a super-objective for any given periods of time—by the minute, hour, day, week, month, year, lifetime, many lifetimes…etc. For example, today I am driven by the lifetime goal of staying alive for as long as possible and as healthy as possible; therefore, I decide to go out for a jog in the morning (we do not really care at this point about the logical entailment of jogging to health). So now I am driven by another objective—go out and run. In order to do this, I must have the proper running clothes on, which means that now changing my clothes is a more immediate objective, which, in order to achieve, I must first get my butt off of this chair…

This is basically a dramatic structure. In a really well written play, the achieving of seemingly simple objectives are often challenged and inhibited by the actions of an antagonist, or plain bad luck from nature. The protagonist, the hero, then must overcome the obstacles, which only seemingly get worse and elevate tension. Eventually all may be solved and returned to a natural state, or it may not. Likewise, in life, we are the heroes. My objective of going for a jog may run smoothly, which is in turn deemed “not dramatic,” but worse yet is if I did not have an objective at all and remain in my chair for the running time of the show (my lifetime!? Scary thoughts!)

In a play, if the characters have no objective, the audience will fall asleep—they want what the hero/heroin wants. Contrarily, if my jogging plan was delayed by an unexpected phone call, which I hurriedly answered and put off, then I felt too hungry, so I want to grab food but is met with the dilemma of running unhealthily after eating, so I go out without eating but is then met with natural disaster—a tornado blows me away… many hours later, I return home with all the exercise that I ever wanted, and exclaim, “what a dramatic day!”

…So it turns out that drama is more so part of our lives than we realize, and it does not even have to relate to whether what we do is exciting—anything can be dramatic! It is only imperative that we stare at the world, at the people going about their daily choirs, at ourselves, and at the motivations of all the behaviors with a dramatic eye-glass, and it is precisely our ability to do so that sets us apart from any other species on this planet.

2010年4月20日星期二

#7 The Film Director (self-created project)

Becoming a director is perhaps the goal of many film production team members, and it is also a dream of mine; however, this is definitely no easy task. The director indubitably has the most difficult job among all above- and below-the-line crew members in a film production team. While the producer is responsible for most of the administrative works and financial decisions of a production and while the sub-directors are responsible for their each individual job discipline, the director (executive) is the liaison among all of these managing and creative personals and is ultimately the person whose vision will become the final product.

When an idea, perhaps a screenwriter’s work, is selected by a producer who plans to produce, a director will be hired. The producer, or in more cases the director, is then responsible for hiring the sub-categorized directors and designers, such as assistant directors, casting director, director of photography, director of audiography, production designer, lighting designer, costume designer…etc., who in turn hire people they are familiar with to serve in their team. Although these highly creative individuals do their jobs mainly by their own decisions, the director ultimately has the approval power.

The first most important stage of the director’s job is the planning stage during pre-production. This is arguably where most if not all of the creative decisions are made by the director. Although some directors agree to leave room for improvisation and planning on the go, most prefer to have the plan to be quite exact for later execution. The reason that this is so is that the more clear the vision, the more time and money it saves on set (some actors are expensive! It is not a good idea waste their time planning shots on set) during the production stage, let alone making the editors’ job easy by providing all the possibly foreseen footage that may have been necessary. The most extreme case for this is Alfred Hitchcock, who claims that all creativity ends the moment he gets up from his desk (during the planning stage). He is perhaps one of the most powerful visionaries when it comes to planning the production. The better the plan, the easier it is to have total control over the production, and this usually results in a better production overall.

After the planning stage, the team goes on set to begin the shoot. This is perhaps what most audience perceives as the true process of making a movie. In fact, this stage goes quite fast if the aforementioned planning stage is done productively. This is “the show” where the director puts his vision into reality by capturing the action onto the camera. From my experience in directing my own student productions, I find it crucial to be accustomed to shooting footage while imagining the final production because they are often quite different with much modification during the post-production stage. To have the editors’ job in mind while also compromising for realistic challenges the camera crew may run into but still maintaining the large bulk of the vision is the director’s great challenge at this point. A great director tells the story, advance the plot, and enchant the audience not by a narration of “camera following protagonist” but rather by the cuts—the juxtaposition of pictures that logically progress a conceivable story in the audience’s minds, relying on the gestalt theory. This is usually what separates a good director from a bad one and is perhaps what separates an enthralling movie from a boring one.

While I cannot quite envisage a detailed description of how this works or how it should work, another important point to mention during the production stage is the director’s interactions with the actors. A director “directs” the actors and tells them what to do, right? Sure, but what does the director tell them? I find it useful, in my amateurish productions, to limit the actors’ urge to “act,” in the commonly viewed sense. I want to tell the story, advance the plot and demonstrate character attributes with cuts, and how well these are done is inferred by how well my cuts are done—none of these has to do with the actors’ abilities to “act,” or to put through their own emotions, or worse yet their own interpretations of the script and thus the conjured emotions. Although this may have been the way theater actors work, film must operate differently since the director now has the tool of the screen, which impacts the traditional part of acting greatly.

In a nutshell, in theater the story is told by the actors’ acting and stage movement, while in film the story is told by cuts. While not doing “line reading” (monkey see, monkey do kind of acting out for the actors, which is usually seen as an insult), the film director can consolidate with the actors about what the vision for this scene is, and the scene is typically motivated by the character’s goal, which is also the audience’s goal. While welcoming suggestions from experienced actors and possibly bringing about a modification to the vision, the director must make sure that the actor behaves in the most simplistic, or uninteresting way, so as to not distract the audience from the story. After all the good stuff is “in the can,” the post-production stage begins.

Editing can be as creative as the planning and shooting stage—the product may turn out all the more different but all the more polished from the raw footages thanks to post editing. This is also where the cuts, previously planned and executed, are assembled into the final envisioned storytelling. Also, it becomes semi-clear at this point how good of a job the director did in the previous stages—does the director have all the potentially useful shots at his/her disposal for assembly, or are there many places where he/she must exclaim, “ah! I wish I had a shot of XXX at this point for insert!” Good planning really pays off at this point, and the editor will love the good director.

After editing and polishing the film, with any special effect inserted. The considered finished production is viewed by the producer for any further modification. It is then rendered and distributed under the duties of the producer who should at this point have sufficiently marketed the product. The director, then, will have the luxury of welcoming the glories of his/her work—and hope the critics take it easy on him/her!

When an idea, perhaps a screenwriter’s work, is selected by a producer who plans to produce, a director will be hired. The producer, or in more cases the director, is then responsible for hiring the sub-categorized directors and designers, such as assistant directors, casting director, director of photography, director of audiography, production designer, lighting designer, costume designer…etc., who in turn hire people they are familiar with to serve in their team. Although these highly creative individuals do their jobs mainly by their own decisions, the director ultimately has the approval power.

The first most important stage of the director’s job is the planning stage during pre-production. This is arguably where most if not all of the creative decisions are made by the director. Although some directors agree to leave room for improvisation and planning on the go, most prefer to have the plan to be quite exact for later execution. The reason that this is so is that the more clear the vision, the more time and money it saves on set (some actors are expensive! It is not a good idea waste their time planning shots on set) during the production stage, let alone making the editors’ job easy by providing all the possibly foreseen footage that may have been necessary. The most extreme case for this is Alfred Hitchcock, who claims that all creativity ends the moment he gets up from his desk (during the planning stage). He is perhaps one of the most powerful visionaries when it comes to planning the production. The better the plan, the easier it is to have total control over the production, and this usually results in a better production overall.

After the planning stage, the team goes on set to begin the shoot. This is perhaps what most audience perceives as the true process of making a movie. In fact, this stage goes quite fast if the aforementioned planning stage is done productively. This is “the show” where the director puts his vision into reality by capturing the action onto the camera. From my experience in directing my own student productions, I find it crucial to be accustomed to shooting footage while imagining the final production because they are often quite different with much modification during the post-production stage. To have the editors’ job in mind while also compromising for realistic challenges the camera crew may run into but still maintaining the large bulk of the vision is the director’s great challenge at this point. A great director tells the story, advance the plot, and enchant the audience not by a narration of “camera following protagonist” but rather by the cuts—the juxtaposition of pictures that logically progress a conceivable story in the audience’s minds, relying on the gestalt theory. This is usually what separates a good director from a bad one and is perhaps what separates an enthralling movie from a boring one.

While I cannot quite envisage a detailed description of how this works or how it should work, another important point to mention during the production stage is the director’s interactions with the actors. A director “directs” the actors and tells them what to do, right? Sure, but what does the director tell them? I find it useful, in my amateurish productions, to limit the actors’ urge to “act,” in the commonly viewed sense. I want to tell the story, advance the plot and demonstrate character attributes with cuts, and how well these are done is inferred by how well my cuts are done—none of these has to do with the actors’ abilities to “act,” or to put through their own emotions, or worse yet their own interpretations of the script and thus the conjured emotions. Although this may have been the way theater actors work, film must operate differently since the director now has the tool of the screen, which impacts the traditional part of acting greatly.

In a nutshell, in theater the story is told by the actors’ acting and stage movement, while in film the story is told by cuts. While not doing “line reading” (monkey see, monkey do kind of acting out for the actors, which is usually seen as an insult), the film director can consolidate with the actors about what the vision for this scene is, and the scene is typically motivated by the character’s goal, which is also the audience’s goal. While welcoming suggestions from experienced actors and possibly bringing about a modification to the vision, the director must make sure that the actor behaves in the most simplistic, or uninteresting way, so as to not distract the audience from the story. After all the good stuff is “in the can,” the post-production stage begins.

Editing can be as creative as the planning and shooting stage—the product may turn out all the more different but all the more polished from the raw footages thanks to post editing. This is also where the cuts, previously planned and executed, are assembled into the final envisioned storytelling. Also, it becomes semi-clear at this point how good of a job the director did in the previous stages—does the director have all the potentially useful shots at his/her disposal for assembly, or are there many places where he/she must exclaim, “ah! I wish I had a shot of XXX at this point for insert!” Good planning really pays off at this point, and the editor will love the good director.

After editing and polishing the film, with any special effect inserted. The considered finished production is viewed by the producer for any further modification. It is then rendered and distributed under the duties of the producer who should at this point have sufficiently marketed the product. The director, then, will have the luxury of welcoming the glories of his/her work—and hope the critics take it easy on him/her!

2010年4月19日星期一

#6 Film Critique

FILM CRITIQUE

Redbelt (2008)

Witten/Directed by David Mamet

While a documentary or a piece of literature can justifiably be character-based and character-driven narrations, a film demands more craftiness in the juxtaposing of the pictures, ultimately called “cuts” in film jargon, that move the story along in the most captivating manner. If the sequence of these shots progress in a most logical and informational way, the audience is likely put to sleep because they are simply provided with more information than they ask for. Mr. Mamet has always had a philosophy of film-making that demands straight-to-the-point sequences, focusing not on expanding on the character but focusing on what the character wants—and ultimately, that is what the audience wants. He makes each “act” in his film focus on the habitual actions, or ultimately what he believes as character, and rightly so.

Redbelt begins with Brazilian jujitsu trainer Mike Terry (Chiwetel Ejiofor) teaching an advanced class in his studio, located in Los Angeles. He has developed a special philosophy for a sparring match—three marbles, two white and one black, are drawn by the two fighters, and the one who draws the black marble gets a handicap in the fight, something like an arm or both arms bound to the body. Through this practice, he hopes to get the point across that it is not the one with an arm bound who has the handicap but the one who underestimates the opponent because of it. He firmly believes that there is no bad situation where one cannot escape from. As the film progresses, it can be observed from his many behaviors and choices of action that he holds strong ground for his moral standards and value assumptions. He does not believe in competition but rather that his craft is used for defense.

However, bad things happen, as they always do in any dramatic structure, whether they are coincidental or planned. After a series of heart-breaking double crossing by a promising-to-help film maker and producer, whom he protected in a bar-fight scenario, Mike’s original monetary issue elevates to monetary crisis, and his training philosophy is stolen without acknowledgement or royalty paid to him. Worse yet, his wife, feeling the financial stress, is part of the plan that betrays him for money. The conflict is elevated to the max when his black-belt student, Joe (Max Martini), commits suicide in an effort to protect the honor of his teacher. Mike’s philosophy that was established in the beginning of the film comes back to haunt him—he may have been able to escape from any kind of arm lock, but can he escape from this much more permanent and real situation? In a final battle, he wins honor and respect from the great Brazilian master himself, but not much can be certain beyond this point.

According to Mr. Mamet’s ideal film formula, the story begins with chaos and ends with order, and the process is the restoration of such order. Unfortunately, although in this film I feel great chaos at the beginning, with some things clearing up during the process, the ending is still a chaotic and ambiguous one, and it is not one of those artistic and beautiful imagination-provoking ambiguities. There comes no resolution in terms of Mike’s financial status, no restoration of the great chaos that he has caused, and no entailment of what consequences the double-crossers may need to pay because of the protagonist’s righteous and courageous actions. The audience (or me at least) is left in a speechless gaze at the screen that should be showing all these but instead have credits rolling too prematurely.

Despite the ambiguous ending debate, my impression of the movie is largely positive. It is one of those films where the story and the super-objectives of each act dominate audience attention. Each scene mainly consists of concise cuts that convey the idea of each sequence in the least informational way—the audience gets the idea but is not bored by the overbearing narrative or blank-filling. The way this movie is planned out and edited proves efficient to communicate the plot and intriguing as a dramatic structure.

Chiwetel Ejiofor shines as the acting protagonist. This British actor delivers his lines quite well, even though the lines he delivers are often put under trial as to whether they live up to his standards. Ejiofor simply has a pleasurable atmosphere to him, whether it is his poised physique or that gentle yet unfathomable psyche. His immense yet calming presence resonates with the overall tone of the movie well, which should be a big point scored by the casting director. With this addition of a brilliant actor, the lack of prominence in the sets and other technical aspects of the film seem neglectable. After all, the film presents the story in a way that left little spaces for the audience and critic alike to wonder their minds off to other things.

Overall Grade: B

Story: B-

Acting: B+ (If there was only Mr. Ejiofor, I would have given an A)

Directing: A-

Visuals: B-

Redbelt (2008)

Witten/Directed by David Mamet

While a documentary or a piece of literature can justifiably be character-based and character-driven narrations, a film demands more craftiness in the juxtaposing of the pictures, ultimately called “cuts” in film jargon, that move the story along in the most captivating manner. If the sequence of these shots progress in a most logical and informational way, the audience is likely put to sleep because they are simply provided with more information than they ask for. Mr. Mamet has always had a philosophy of film-making that demands straight-to-the-point sequences, focusing not on expanding on the character but focusing on what the character wants—and ultimately, that is what the audience wants. He makes each “act” in his film focus on the habitual actions, or ultimately what he believes as character, and rightly so.

Redbelt begins with Brazilian jujitsu trainer Mike Terry (Chiwetel Ejiofor) teaching an advanced class in his studio, located in Los Angeles. He has developed a special philosophy for a sparring match—three marbles, two white and one black, are drawn by the two fighters, and the one who draws the black marble gets a handicap in the fight, something like an arm or both arms bound to the body. Through this practice, he hopes to get the point across that it is not the one with an arm bound who has the handicap but the one who underestimates the opponent because of it. He firmly believes that there is no bad situation where one cannot escape from. As the film progresses, it can be observed from his many behaviors and choices of action that he holds strong ground for his moral standards and value assumptions. He does not believe in competition but rather that his craft is used for defense.

However, bad things happen, as they always do in any dramatic structure, whether they are coincidental or planned. After a series of heart-breaking double crossing by a promising-to-help film maker and producer, whom he protected in a bar-fight scenario, Mike’s original monetary issue elevates to monetary crisis, and his training philosophy is stolen without acknowledgement or royalty paid to him. Worse yet, his wife, feeling the financial stress, is part of the plan that betrays him for money. The conflict is elevated to the max when his black-belt student, Joe (Max Martini), commits suicide in an effort to protect the honor of his teacher. Mike’s philosophy that was established in the beginning of the film comes back to haunt him—he may have been able to escape from any kind of arm lock, but can he escape from this much more permanent and real situation? In a final battle, he wins honor and respect from the great Brazilian master himself, but not much can be certain beyond this point.

According to Mr. Mamet’s ideal film formula, the story begins with chaos and ends with order, and the process is the restoration of such order. Unfortunately, although in this film I feel great chaos at the beginning, with some things clearing up during the process, the ending is still a chaotic and ambiguous one, and it is not one of those artistic and beautiful imagination-provoking ambiguities. There comes no resolution in terms of Mike’s financial status, no restoration of the great chaos that he has caused, and no entailment of what consequences the double-crossers may need to pay because of the protagonist’s righteous and courageous actions. The audience (or me at least) is left in a speechless gaze at the screen that should be showing all these but instead have credits rolling too prematurely.

Despite the ambiguous ending debate, my impression of the movie is largely positive. It is one of those films where the story and the super-objectives of each act dominate audience attention. Each scene mainly consists of concise cuts that convey the idea of each sequence in the least informational way—the audience gets the idea but is not bored by the overbearing narrative or blank-filling. The way this movie is planned out and edited proves efficient to communicate the plot and intriguing as a dramatic structure.

Chiwetel Ejiofor shines as the acting protagonist. This British actor delivers his lines quite well, even though the lines he delivers are often put under trial as to whether they live up to his standards. Ejiofor simply has a pleasurable atmosphere to him, whether it is his poised physique or that gentle yet unfathomable psyche. His immense yet calming presence resonates with the overall tone of the movie well, which should be a big point scored by the casting director. With this addition of a brilliant actor, the lack of prominence in the sets and other technical aspects of the film seem neglectable. After all, the film presents the story in a way that left little spaces for the audience and critic alike to wonder their minds off to other things.

Overall Grade: B

Story: B-

Acting: B+ (If there was only Mr. Ejiofor, I would have given an A)

Directing: A-

Visuals: B-

2010年4月12日星期一

#5 Show Report - “passion piece” on my favorite opera

The piece I chose to be passionate about is the opera Rigoletto. My identification with this opera is for a most intriguing and unexpected reason—I have been listening to a particular part of it repeatedly before, since my elementary school years, in a video game (Counter-Strike, the Italy map), without knowing its original context; therefore, when I actually watched the opera, I immediately recognized the segment, called “E Il Sol Dell'anima,” and consequently felt a great wave of awe and satisfaction. Besides this fact, Rigoletto is still a very fun opera, with captivating plot and great music.

Rigoletto was written by Giuseppe Verdi, in the 1850’s, and was considered his first real opera masterpiece among his mid-to-late career works. The story is about Rigoletto, the Duke of Mantua’s jester, who consistently picks on the Duke’s court members with “a tongue like an assassin’s dagger.” The Duke of Mantua, a notorious womanizer, seduces Rigoletto’s daughter, who was then kidnapped by the Duke’s court members who had a grudge on Rigoletto for his insults. Rigoletto hires an assassin to kill the Duke, and through a series of mishaps Rigoletto’s daughter dies in place of the Duke, with the Duke singing away, “woman is fickle…”

The opera is a great sarcastic masterpiece—there exist several satirical plot points within the opera that should be examined in detail. The major notion is the inconsistencies between Duke’s attitudes towards women and of women. Being an irresponsible womanizer, the Duke scores with various women; in fact, at the beginning of the opera, he sings about what a wonderful nature of life it is to be able to have pleasure with as many women as possible. Throughout the play, he woos Rigoletto’s daughter, who was a well-protected and innocent woman. She gives him her heart, unaware of his vile nature with women. Later, he seduces the assassin’s sister, who in turn pleads for his life to her brother, who eventually killed Rigoletto’s daughter as a substitute for his planned death ordered by Rigoletto himself. The great irony in this is that as this twisted plotline goes on—the most innocent one dies, and the most responsible one lives, singing “woman is fickle” because according to him, women are not to be trusted in romance.

To further the irony of this “coincidence,” “woman is fickle” had a most catchy tune. It was prospected that the audience at that time likely left the opera house whistling “woman is fickle,” as opposed to some of the other melodies, such as ones where they expressed love between man and woman, father and daughter, etc. Why is it so? Why is it that the most hypocritical themed song was the most attention-keeping and popular? Does this imply somewhat the value assumptions of their society concerning relationships between men and women? A deeper social introspection should have been called for.

Another satirical point relates to Rigoletto—his character flaws are ultimately responsible for his daughter’s death, a devastating tragic event to him. He meets the assassin and immediately identifies with him, saying that the assassin kills with swords while he kills with words. His vile attitude and fun-poking toward the court members of the Duke is one of the crucial causes for his daughter’s initial abduction. His hatred, which leads him to the hiring of the assassin, was the second key factor for the tragedy. His over-protection of his daughter, which resulted in his daughter left undefended (too innocent) to the cunning and experienced (at wooing women) Duke, is arguably the reason why she fell hopelessly in love with a man who has no conscience about true love—leading to her eventual sacrifice for the Duke (even though she already knew the Duke’s true nature at the point, that the Duke was wooing the assassin’s sister) and her death. Rigoletto is a typical tragic hero—eventually paying big time for the consequences of his flaws which were proven fatal.

An argument to make at this point, is whether this series of events that lead to the eventual catastrophe is strictly a logical result of the character flaws, or is it fate, and these things happen regardless of what the characters’ traits are? This is an intriguing thought because the answer to this question usually directly affects some people’s attitudes in everyday lives. The former belief usually results in a more responsible and up-beat attitude—the belief that one has the power to influence his/her own fate. The latter is more passive—leaving the path into the hands of the supernatural.

Being a firm disbeliever in fate, I resonate with the first idea greatly, which is ultimately why I like the opera—it packs the message that if one acts in faulty ways, there will be consequences. I personally identify with the theme of the opera, which was quite impressive for the age in history when fate was still a dominant force influencing people’s lives.

Rigoletto was written by Giuseppe Verdi, in the 1850’s, and was considered his first real opera masterpiece among his mid-to-late career works. The story is about Rigoletto, the Duke of Mantua’s jester, who consistently picks on the Duke’s court members with “a tongue like an assassin’s dagger.” The Duke of Mantua, a notorious womanizer, seduces Rigoletto’s daughter, who was then kidnapped by the Duke’s court members who had a grudge on Rigoletto for his insults. Rigoletto hires an assassin to kill the Duke, and through a series of mishaps Rigoletto’s daughter dies in place of the Duke, with the Duke singing away, “woman is fickle…”

The opera is a great sarcastic masterpiece—there exist several satirical plot points within the opera that should be examined in detail. The major notion is the inconsistencies between Duke’s attitudes towards women and of women. Being an irresponsible womanizer, the Duke scores with various women; in fact, at the beginning of the opera, he sings about what a wonderful nature of life it is to be able to have pleasure with as many women as possible. Throughout the play, he woos Rigoletto’s daughter, who was a well-protected and innocent woman. She gives him her heart, unaware of his vile nature with women. Later, he seduces the assassin’s sister, who in turn pleads for his life to her brother, who eventually killed Rigoletto’s daughter as a substitute for his planned death ordered by Rigoletto himself. The great irony in this is that as this twisted plotline goes on—the most innocent one dies, and the most responsible one lives, singing “woman is fickle” because according to him, women are not to be trusted in romance.

To further the irony of this “coincidence,” “woman is fickle” had a most catchy tune. It was prospected that the audience at that time likely left the opera house whistling “woman is fickle,” as opposed to some of the other melodies, such as ones where they expressed love between man and woman, father and daughter, etc. Why is it so? Why is it that the most hypocritical themed song was the most attention-keeping and popular? Does this imply somewhat the value assumptions of their society concerning relationships between men and women? A deeper social introspection should have been called for.

Another satirical point relates to Rigoletto—his character flaws are ultimately responsible for his daughter’s death, a devastating tragic event to him. He meets the assassin and immediately identifies with him, saying that the assassin kills with swords while he kills with words. His vile attitude and fun-poking toward the court members of the Duke is one of the crucial causes for his daughter’s initial abduction. His hatred, which leads him to the hiring of the assassin, was the second key factor for the tragedy. His over-protection of his daughter, which resulted in his daughter left undefended (too innocent) to the cunning and experienced (at wooing women) Duke, is arguably the reason why she fell hopelessly in love with a man who has no conscience about true love—leading to her eventual sacrifice for the Duke (even though she already knew the Duke’s true nature at the point, that the Duke was wooing the assassin’s sister) and her death. Rigoletto is a typical tragic hero—eventually paying big time for the consequences of his flaws which were proven fatal.

An argument to make at this point, is whether this series of events that lead to the eventual catastrophe is strictly a logical result of the character flaws, or is it fate, and these things happen regardless of what the characters’ traits are? This is an intriguing thought because the answer to this question usually directly affects some people’s attitudes in everyday lives. The former belief usually results in a more responsible and up-beat attitude—the belief that one has the power to influence his/her own fate. The latter is more passive—leaving the path into the hands of the supernatural.

Being a firm disbeliever in fate, I resonate with the first idea greatly, which is ultimately why I like the opera—it packs the message that if one acts in faulty ways, there will be consequences. I personally identify with the theme of the opera, which was quite impressive for the age in history when fate was still a dominant force influencing people’s lives.

2010年4月11日星期日

#4 Relate Theater to your Major or Minor.

Let me begin with a simple statement about the status of my major—I am a member of the communications media department student body. Having said this, it really does not provide a great deal of information, since there are still many more branches of specializations, disciplines, or just plainly different areas of study. Within the communications department exist focuses such as radio production, television production, audio mixing, animations, cooperate training, human recourses, media psychology and theories… It would not be practical to master all of these fields simply because I am a Comm. Media student, and there is no motivation for such action either. Therefore, to further clarify just what do I plan to do, I must take a slight digression toward the paths which I have taken to arrive at my state today (yes that sounds like boredom, but please bear with me).

As a child, I was fascinated with the world of animations—American cartoons, traditional Chinese paper shadow animations, Chinese paint animations or claymations, Japanese anime, and such. I enjoyed drawing cartoon figures as I grew up. Although I never had any formal training in the arts of drawing cartoons, my style and skill evolves and matures as I do. Eventually, I arrived at a point where I was seriously considering becoming an animator. At this point, you probably think that I was one of those prodigy kids who learn on their own to arrive at great success, solely dependent on their self-training. Well, that is not exactly what turned out—it seems that as I grow up even more, I began to face the inevitable decision to distinguish interest and hobby from profession. I found out, that due to the lack of formal training, my skills are simply not up to industry standards for animators.

However, this really is not the crucial factor for my change of decision. The more important thing is, as I transform from a kid to an adult, my career goal also somewhat transformed—from animations to films (ironically, these seem to be similar media but the former seen as directed toward kids and latter toward adults). After a series of serious self-reflective sessions, I realized that my love for animations may be based on the animations’ cinematic nature in the first place! Therefore, after a few tackles at shooting short films for a video production class, I was able to confirm my goal. I wanted to go into the film industry.

…Which is why I am here, today, enrolled in a theater class and will continuously participate in a series of theater classes. Even though I am a Comm. Media major, I value the importance of being well trained in a variety of crafts—ranging from the basic studies of humanity to the visual arts, and now, to theater. Now that I have a more definite goal, I can more clearly choose the classes most useful for the path that I take. At this point, one may say, well sure, you must be in the right place for choosing theater classes! Yes, and no.

Theater and cinema share a great deal of commonalities—such as the creative process, aesthetic values, conventions, representational nature of the performance…etc., but there are also a great deal of differences. To be able to successfully utilize knowledge obtained in theater classes, I must set a goal to fully identify and understand the differences between theater and film. Right now, I am at a stage where I can identify the more basic differences. For example, the film director has at his disposal the tool of the camera lens and all the nice features and possibilities that come with the lens, such as editing and effects. The audience view film through a screen, therefore granting the film director more control over what the audience sees and how that affects the experience. On the other hand, the theater artists enjoy more thrill of the live aspect of the performance. They must sometimes even improvise at the spot, which means that they are generally under less director control or supervision—there really is no post-production in theater the actors ultimately have the final control over what the audience sees, not the editor. I could name many more aspects where the two media are different; however, I am by no means an expert in either, which is why I wish to learn, in more depth and detail, the crafts of both.

It can be said that my path ahead is a truly intriguing and exciting one!

As a child, I was fascinated with the world of animations—American cartoons, traditional Chinese paper shadow animations, Chinese paint animations or claymations, Japanese anime, and such. I enjoyed drawing cartoon figures as I grew up. Although I never had any formal training in the arts of drawing cartoons, my style and skill evolves and matures as I do. Eventually, I arrived at a point where I was seriously considering becoming an animator. At this point, you probably think that I was one of those prodigy kids who learn on their own to arrive at great success, solely dependent on their self-training. Well, that is not exactly what turned out—it seems that as I grow up even more, I began to face the inevitable decision to distinguish interest and hobby from profession. I found out, that due to the lack of formal training, my skills are simply not up to industry standards for animators.

However, this really is not the crucial factor for my change of decision. The more important thing is, as I transform from a kid to an adult, my career goal also somewhat transformed—from animations to films (ironically, these seem to be similar media but the former seen as directed toward kids and latter toward adults). After a series of serious self-reflective sessions, I realized that my love for animations may be based on the animations’ cinematic nature in the first place! Therefore, after a few tackles at shooting short films for a video production class, I was able to confirm my goal. I wanted to go into the film industry.

…Which is why I am here, today, enrolled in a theater class and will continuously participate in a series of theater classes. Even though I am a Comm. Media major, I value the importance of being well trained in a variety of crafts—ranging from the basic studies of humanity to the visual arts, and now, to theater. Now that I have a more definite goal, I can more clearly choose the classes most useful for the path that I take. At this point, one may say, well sure, you must be in the right place for choosing theater classes! Yes, and no.

Theater and cinema share a great deal of commonalities—such as the creative process, aesthetic values, conventions, representational nature of the performance…etc., but there are also a great deal of differences. To be able to successfully utilize knowledge obtained in theater classes, I must set a goal to fully identify and understand the differences between theater and film. Right now, I am at a stage where I can identify the more basic differences. For example, the film director has at his disposal the tool of the camera lens and all the nice features and possibilities that come with the lens, such as editing and effects. The audience view film through a screen, therefore granting the film director more control over what the audience sees and how that affects the experience. On the other hand, the theater artists enjoy more thrill of the live aspect of the performance. They must sometimes even improvise at the spot, which means that they are generally under less director control or supervision—there really is no post-production in theater the actors ultimately have the final control over what the audience sees, not the editor. I could name many more aspects where the two media are different; however, I am by no means an expert in either, which is why I wish to learn, in more depth and detail, the crafts of both.

It can be said that my path ahead is a truly intriguing and exciting one!

2010年4月6日星期二

#3 Costume Design

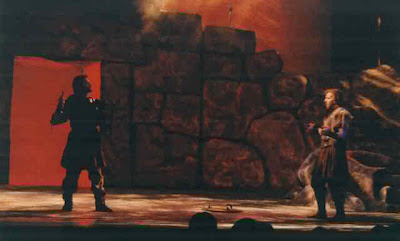

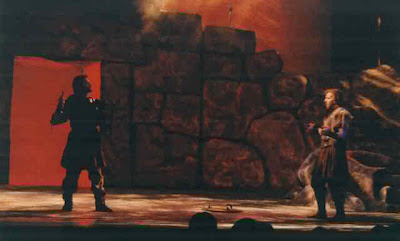

For my costume design project, I selected the play Macbeth by William Shakespeare. I focus on the scene of the duel between Macbeth and Macduff and the eventual slaying of Macbeth. (Act V, Scenes 10 & 11). And for my research, I will focus on Macbeth’s costumes.

I have a selection of references from stage play to movie adaption, where the concepts behind the costumes varied moderately. Some depict him as wearing a robe and crown at all times, even during the fight scene, while others depict him wearing proper armor and helmet during the fight but not so when he is not fighting. There are also some more “modern” versions of Macbeth, with the most modern version (not shown in this project!) as modern army men version and even Star War with light saber style.

After viewing various images of design, the few components of the costume can be listed as:

• Cape (regular textile or with fur)

• Robe (longer/shorter ones)

• Belt (somewhat luxurious, decorated with charms and hilt for sword)

• Baggy-sleeved shirt (while in some other versions, sleeveless)

• Body Armor (leather or metal, some have arm plates or leg plates)

• Lower body ties/kilts (fabric material similar to the robe)

• Baggy pants (material similar to the shirt)

• Boots (black leather boots/brown dirt boots)

• Weapons: dagger, sword, shield

The appearance of Macbeth has several popular versions—bearded or unbearded. His hair can be at various lengths. Interestingly, the age depiction also varied a bit—some versions had a younger Macbeth while others have older versions.

I will create two renderings of Macbeth—one of which more dignifiedly dressed, with proper king robes and a more mastermind kind of appearance. This is the sly Macbeth, absorbed within his own cruel implementation of evil plans. Body armor is kept at a minimum in this version. The other rendering portrays him in a more savage way—less robe, more armor. This is the Macbeth with his ambition at full strength—he is zealous and in a frenzy to kill all who oppose him.

I have a selection of references from stage play to movie adaption, where the concepts behind the costumes varied moderately. Some depict him as wearing a robe and crown at all times, even during the fight scene, while others depict him wearing proper armor and helmet during the fight but not so when he is not fighting. There are also some more “modern” versions of Macbeth, with the most modern version (not shown in this project!) as modern army men version and even Star War with light saber style.

After viewing various images of design, the few components of the costume can be listed as:

• Cape (regular textile or with fur)

• Robe (longer/shorter ones)

• Belt (somewhat luxurious, decorated with charms and hilt for sword)

• Baggy-sleeved shirt (while in some other versions, sleeveless)

• Body Armor (leather or metal, some have arm plates or leg plates)

• Lower body ties/kilts (fabric material similar to the robe)

• Baggy pants (material similar to the shirt)

• Boots (black leather boots/brown dirt boots)

• Weapons: dagger, sword, shield

The appearance of Macbeth has several popular versions—bearded or unbearded. His hair can be at various lengths. Interestingly, the age depiction also varied a bit—some versions had a younger Macbeth while others have older versions.

I will create two renderings of Macbeth—one of which more dignifiedly dressed, with proper king robes and a more mastermind kind of appearance. This is the sly Macbeth, absorbed within his own cruel implementation of evil plans. Body armor is kept at a minimum in this version. The other rendering portrays him in a more savage way—less robe, more armor. This is the Macbeth with his ambition at full strength—he is zealous and in a frenzy to kill all who oppose him.

#2 Research an important theatre artist or playwright

This is a research project; therefore, I felt obligated to research an artist with whom I was not familiar with; however, this is also a reflection project, which means that I must have some connections or identifications with the artist. After a short hesitation, I decided to go with everyone’s favorite—William Shakespeare.

How is Shakespeare important for theater today? In about a million ways! His works are the models and goals playwrights today look up to—they set a standard for classic plays and an extremely high standard too. His other major contribution is the fact that he is so famous and his works so astonishing, he becomes a representational figure for theater throughout history (after he was born, of course) and across the globe. If you wanted to study theater and plays—Shakespeare is the man to start with; if you wanted to just read theater literature—Shakespeare’s works are where to begin. He is prominent to the theater world enough to become an icon, and that’s important to unite this considerably diverse art together.

Western style plays are not enjoyed everywhere, but Shakespeare is truly the penetrating factor for Western plays, specifically English plays, to other cultures. In China, I have heard of Shakespeare at an age comparable to when English or American Children hear about him. I also presume, with a decent level of confidence, that a same (if not higher!) percentage of the educated population in China knows Shakespeare as comparing to Western cultures. Although I cannot speak for many of the other non-Western cultures, and certainly cannot even represent the Chinese population, but still, what does this tell us? I believe that this carries about precisely this message, that Shakespeare is no longer just an Englishman, he is a global existence.

I would like to go through an internal actualization of my identification with Shakespeare through the examination of the process of which I was educated about him. My dad was a professor of the English Literature in a Chinese university, so naturally, I was hearing about Shakespeare a bit more often than my peers. At a young age, I only had the comprehension that this is an extremely famous person. I knew about a few of his works, and we studied segments of the translated version in class (elementary school Chinese class text). We knew that Romeo and Juliet was basically a metaphor for lovers who cannot end up together because of external opposing forces, and that Macbeth was a symbol of greedy ruler breaking his own toes with his own large stone, and that Hamlet was full of the supernatural and vengeance… but the literature itself was still beyond my ability. So although it can be said that I “grew up” with him, I did not comprehend much of his stuff until I was a bit older.

Later on, when my focus on him became much more academic, even professional, I was faced with the complexity of the variety of his works—of course, there weren’t just plays, but also poems. The meaning of the content was secondary, and the more arbitrary rules of interpreting his works came in—I had to learn about iambic pentameters and the structures of play acts and scenes (if it was a movie, also shots). It was no longer limited to learning the plot and the story but about the language itself—which was a stage where it became clearly distinguishable that he was different from any other storyteller. However, the study to this point focused on the merits of the literature of his work—there wasn’t much theater involved yet.

Finally, up to now, after educating myself with the proper ideas behind theater, I can finally take a look at his works under a (somewhat) complete light. His works, now as I see them, cannot be limited to merely words, but must incorporate also the elements of theater, such as staging, lighting, blocking, costumes, acting…etc, which all help elevate his works’ greatness to a new height. Different productions of the same play, for example, can also provide variety to what his original intentions were—a brand new dimension is added to it when we visualize literature to turn it into theater.

This leads me to the drawing of my conclusion—I now realize that his true greatness lies within not only the literature that he has left behind but also the invaluable treasure for the world of theater—the infinite possibilities of working with great theatrical work. As a potential film maker of the future, I do not wish to possibly fully comprehend his literary heights, but his insights and the harmonious relationship between his written compendium and the production of these works into a visual experience proves to be a priceless treasure.

How is Shakespeare important for theater today? In about a million ways! His works are the models and goals playwrights today look up to—they set a standard for classic plays and an extremely high standard too. His other major contribution is the fact that he is so famous and his works so astonishing, he becomes a representational figure for theater throughout history (after he was born, of course) and across the globe. If you wanted to study theater and plays—Shakespeare is the man to start with; if you wanted to just read theater literature—Shakespeare’s works are where to begin. He is prominent to the theater world enough to become an icon, and that’s important to unite this considerably diverse art together.

Western style plays are not enjoyed everywhere, but Shakespeare is truly the penetrating factor for Western plays, specifically English plays, to other cultures. In China, I have heard of Shakespeare at an age comparable to when English or American Children hear about him. I also presume, with a decent level of confidence, that a same (if not higher!) percentage of the educated population in China knows Shakespeare as comparing to Western cultures. Although I cannot speak for many of the other non-Western cultures, and certainly cannot even represent the Chinese population, but still, what does this tell us? I believe that this carries about precisely this message, that Shakespeare is no longer just an Englishman, he is a global existence.

I would like to go through an internal actualization of my identification with Shakespeare through the examination of the process of which I was educated about him. My dad was a professor of the English Literature in a Chinese university, so naturally, I was hearing about Shakespeare a bit more often than my peers. At a young age, I only had the comprehension that this is an extremely famous person. I knew about a few of his works, and we studied segments of the translated version in class (elementary school Chinese class text). We knew that Romeo and Juliet was basically a metaphor for lovers who cannot end up together because of external opposing forces, and that Macbeth was a symbol of greedy ruler breaking his own toes with his own large stone, and that Hamlet was full of the supernatural and vengeance… but the literature itself was still beyond my ability. So although it can be said that I “grew up” with him, I did not comprehend much of his stuff until I was a bit older.

Later on, when my focus on him became much more academic, even professional, I was faced with the complexity of the variety of his works—of course, there weren’t just plays, but also poems. The meaning of the content was secondary, and the more arbitrary rules of interpreting his works came in—I had to learn about iambic pentameters and the structures of play acts and scenes (if it was a movie, also shots). It was no longer limited to learning the plot and the story but about the language itself—which was a stage where it became clearly distinguishable that he was different from any other storyteller. However, the study to this point focused on the merits of the literature of his work—there wasn’t much theater involved yet.

Finally, up to now, after educating myself with the proper ideas behind theater, I can finally take a look at his works under a (somewhat) complete light. His works, now as I see them, cannot be limited to merely words, but must incorporate also the elements of theater, such as staging, lighting, blocking, costumes, acting…etc, which all help elevate his works’ greatness to a new height. Different productions of the same play, for example, can also provide variety to what his original intentions were—a brand new dimension is added to it when we visualize literature to turn it into theater.

This leads me to the drawing of my conclusion—I now realize that his true greatness lies within not only the literature that he has left behind but also the invaluable treasure for the world of theater—the infinite possibilities of working with great theatrical work. As a potential film maker of the future, I do not wish to possibly fully comprehend his literary heights, but his insights and the harmonious relationship between his written compendium and the production of these works into a visual experience proves to be a priceless treasure.

订阅:

评论 (Atom)